In the Indian city of Benares, beneath a dome that marks the center of the world, is a brass plate in which are set three diamond needles, each as thick as a bee and a cubit high. At the time of creation Brahma placed on one of these needles 64 disks of pure gold, each a different size, each resting only on plates of a larger size (so the largest disk was at the bottom and the smallest at the top).

In the temple are priests whose task is to transfer all the disks to a different needle, moving only one disk at a time between needles but never placing a larger disk on top of a smaller one. When the task is done, tower, temple and Brahmins all will vanish with a thunderclap and the world will vanish.

So how much time do we have left?

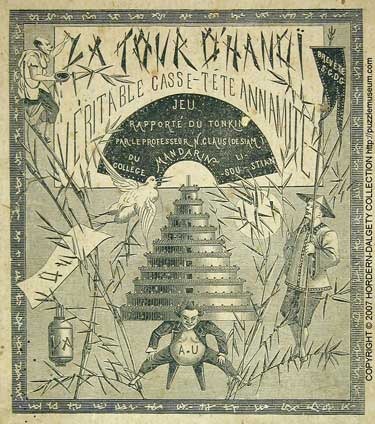

The romantic fable above was popularized (and possibly invented) by one Edouard Lucas to accompany a popular game he invented and sold in 1883, called the Towers of Hanoi. The game itself has only 8 disks (which is fortunate, as we shall see), and is still available today.

When trying to solve the problem, it helps to start small. Obviously if there were no discs, no moves would be needed, and with one disc, just one move is needed. What about two discs? That would require three moves: moving the smallest disc from the “initial” to the “spare” needle, then moving the largest disc to the “target” needles, and finally moving the small disc to the target needle.

Going beyond two discs things are a little less obvious. If we think about the largest disc though, we can note that in order to move the largest disc from the initial to the target pin, we must first move all the other discs to the spare pin. So, if we have n discs, we can state a solution to the n-disc problem thus:

move n-1 discs from the initial to the spare needle, using the target needle as a spare

move disc n (the largest disc) from the initial needle to the target needle

move n-1 discs from the spare needle to the target needle, using the initial needle as a spare

So we have effectively reduced the n disc problem to an n-1 disc problem. If we repeatedly apply this approach, eventually we get to a 1 disc problem which is trivial.

Even though we have “solved” the problem, it is not obvious what the sequence of moves should be for a large number of discs. Nonetheless, the method above works, and describes a formal recipe, commonly known as an algorithm, to solve the problem. Keeping track of the sequence of moves that have been done and still need to be done can be somewhat tedious for a human, but not for a computer, and the method above is often used in computer programs to solve the Towers problem. The algorithm could be written as:

SolveTowers(from, to, using, n)

{

if (n > 0)

{

SolveTowers(from, using, to, n-1);

print "Move disc " + n + " from needle "+from+" to needle "+to;

SolveTowers(using, to, from, n-1);

}

}

If we called the needles A, B and C, and ran the algorithm above with “SolveTowers(A, B, C, 64)” we would get the sequence of moves needed by the monks. Algorithms like the one above, where we break the problem down using a smaller version of itself, are called recursive algorithms.

We still haven’t answered the question of how long it would take, but we’re getting closer. If we call the number of moves needed to solve the n-disc Tower problem \(S_{n}\), then we can see (modeling the steps above):

we need \(S_{n-1}\) moves for the first step

plus one move for disc n

plus \(S_{n-1}\) moves for the last step

In other words \(S_{n} = 2 S_{n-1} + 1\).

This equation needs to stop somewhere to be useful; we know that one disc takes one move so we know that \(S_{1} = 1\). So we can write the complete recursive definition of \(S_{n}\) as:

$$ S_n = \begin{cases} 2S_{n-1} + 1 & \text{if } n > 1, \\ 1 & \text{if } n = 1. \end{cases} $$

Equations like this, where we define sequence terms in terms of earlier sequence terms, are called recurrence relations or difference equations, while known values like \(S_{1} = 1\) that terminate the process are called boundary conditions.

Towers of Hanoi is just one of many recurrence relations. We’ll look at a few more and then look at some general techniques for dealing with these.

For a first example, consider how many pieces you can slice the plane into with a number of lines, where no two lines are parallel and no three intersect at a single point (lines that satisfy these conditions are said to be in general position). The first line will divide the plane in two; the second line will divide it in four, the third in seven, and in general:

$$P_n = P_{n-1} + n$$

where \(P_n\) is the number of pieces after the n’th line. I.e. the \(n^{th}\) line adds \(n\) new pieces. The boundary condition is \(P_{0}=1\).

As another example, consider a population of organisms that takes 2 years to mature after which each pair produces another pair, and continues to do so each year thereafter.

Each newborn pair plus offspring then has an annual population count of 1, 1, 3, 5, 8, 13…, which may be recognized as the Fibonacci sequence:

$$a_n = a_{n-1} + a_{n-2}$$

with boundary conditions \(a_0 = 1, a_1 = 1\).

The problem with these is that in order to compute the value for some \(n\), we have to calculate all values all the way from the boundary condition up to the \(n^{th}\). We’d prefer to just have some function in terms of \(n\).

There are a number of approaches we can use. We can try to find the function by inspection, using some number of terms, and then prove the postulated solution by induction. A related approach is to look at modified versions of the sequence - for example dividing each term by \(n\) - to see if a pattern emerges. Adding a constant to each term before the division may make the pattern more obvious.

If we look at Towers of Hanoi, we can see that the first few terms are 1, 3, 7, 15, 31, 63. So a reasonable postulate is:

$$S_n = 2^n - 1$$

It is easy to prove this by induction:

$$S_{n+1} = 2 S_n + 1 = 2 (2^n - 1) + 1 = 2^{n+1} - 1$$

For the regions of the plane, we can use the second approach. Simple division by \(n\) doesn’t offer a clear pattern, but if we first subtract 1 from each term, i.e. look at the sequence \(\frac{P_n-1}{n}\), we get the sequence 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, …, and a clear pattern emerges. It appears that:

$$\frac{P_n-1}{n} = \frac{n+1}{2}$$

or:

$$P_n = \frac{n (n+1)}{2} + 1$$

Once again by induction:

$$\begin{align} P_{n+1} & = P_n + n + 1 \\ & = (\frac{n (n+1)}{2}+1) + n + 1 \\ & = \frac{n^2 + 2 + 2n}{2} + 1 \\ & = \frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2}+1 \end{align}$$

As for the Fibonacci sequence, that is a topic for another day!